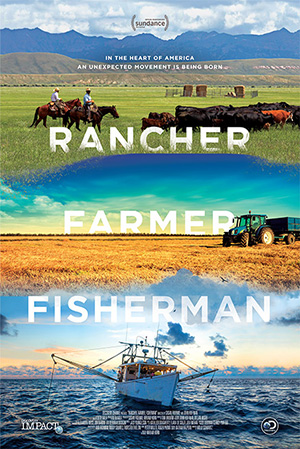

Plant Chat: Miriam Horn, Author of Rancher, Farmer, Fisherman

I’m really happy to have Miriam Horn on my Plant Chat this month. Miriam is an accomplished author, focusing on collaborative and place-based conservation, large-scale sustainable food production, coastal restoration and community impacts. I saw Miriam, who works with the Environmental Defense Fund, speak about the film based on her book Rancher, Farmer, Fisherman, Conservation Heroes of the American Heartland, at the Sustainable Agriculture Summit in Kansas City last fall. Her book profiles a Montana cowboy, Kansas wheat farmer, Louisiana shrimper, Gulf of Mexico red snapper fisherman and the CEO of a barge company that navigates the inland waterways that connect them all—leaders of an unsung movement to protect the nation’s wildlife, rangelands, soils, wetlands, and marine ecosystems. Her previous book on clean energy technologies, co-authored with EDF president Fred Krupp, was a New York Times bestseller and also a Discovery documentary. If you want to learn more about Miriam’s thoughts on the environment, sustainable agriculture, and more, please continue reading our interview.

What are the primary ways in which agriculture has changed in the U.S. over the past 50 years?

Since its beginnings, agriculture has been destructive: first, because, by definition, it displaces an ecosystem and everything that lives within it. And second, because it has nearly always depended on plowing, which turns out to be one of the most destructive things you can do: to soil structure and soil life on the farm, and also beyond the farm–because plowed soil erodes, fails to hold water (which runs off and takes with it nitrogen and chemicals that do harm downstream), and releases carbon into the atmosphere, contributing to climate change.

What changes are being made to address sustainability in the food system?

The farmers we’ve found having the greatest and most far-reaching success in minimizing agriculture’s harms are not artisanal growers serving local markets or romantics reverting to horse-drawn plows but the same farmers often demonized in that conventional story: big, heartland farmers using advanced technologies to grow commodity crops for export to domestic and global markets. These farmers are focused on what matters most: protecting biodiversity, both above ground (birds, pollinators, mammals) and below (the trillions of soil microbes that make up the most critical ecosystem on earth); rebuilding soil carbon; and making the most productive use of each bit of precious water and land they lay claim to—at the expense, they recognize, of its use by other people and other organisms.

Their strategies are highly responsive to the climate and soil types and ecosystems they farm within. Justin Knopf, for instance, the “industrial-scale” Kansas wheat farmer I profile in my book, emulates the prairie he farms within. He hasn’t plowed in 30 years, but leaves his soil and its inhabitants undisturbed and protected under a mat of residues. His move to “no-tilling” has not only put an end to erosion–critical in a region devastated by the Dust Bowl and still losing a billion tons of irreplaceable topsoil each year. It also cools his soils and increases their ability to capture and hold water, both ever more crucial as weather grows more extreme. He grows crops well-suited to his climate and soil types, so needs no irrigation or heated greenhouses (Those water and energy-intensive interventions are often the price of providing tomatoes, asparagus and microgreens to every farmer’s market across America.) He boosts biodiversity by accelerating his crop rotations and also by introducing “cover crops”–mixtures of plants that he never harvests but grows to shade and shelter his soils, feed his soil microbes, bank nutrients like nitrogen for the next crop, provide habitat and thwart pests. And knowing that half of all ice-free land on earth is now given over to producing food, and that every day new ecosystems are sacrificed to agriculture, he maximizes productivity on every acre. Efficiency, in other words, is not a dirty word but a critical measure of a farm’s sustainability. The results are stunningly evident: even as Justin’s yields remain high and steady year after year, intensive tests of his soils reveal carbon levels well on their way back to those of native prairie and a robust and diverse microbial ecology. And he is not an outlier: 20% of heartland farmers are now no-tilling, cutting soil losses by half while they rebuild soil carbon and life.

The sustainability movement has often focused on small, organic, local agriculture within a community, but what are the limitations for this sort of agricultural system within the overall food system? What are the successes of these sorts of agricultural systems?

Justin is not organic, a certification many think is synonymous with “sustainable” but in fact provides little insight into these crucial aspects of stewardship. Those gaps were recently acknowledged by the Rodale Institute–the most important force in the past half century in the rise of organic ag. Many consumers, Rodale wrote, “believe the USDA organic label regulates more than it actually does…it doesn’t go far enough when it comes to ensuring healthy soil, biodiversity and animal welfare.” Rodale has now joined the growing ranks of NGOs and companies working to provide consumers greater insight into the farms supplying their food. Some, like Rodale, are working on a “regenerative” label that would recognize farmers like Justin successfully rebuilding damaged soils.

Whole Foods has developed a “responsibly grown” certification for produce, prioritizing the crucial metrics: soil health; air, energy and climate; waste reduction; farmworker welfare; water conservation and protection; biodiversity (including pollinator habitat); and pest management that (like Justin’s) relies first on biological methods like diverse cropping. Individual food companies like Land O’Lakes are also stepping us as huge forces for good in moving their farmer-members to more sustainable practices. The most innovative emerging effort may be the Noble Growth Network, which is tightening up the supply chain between farmers and food companies. My most unexpected advice might be to shop at Wal-Mart, which has committed to eliminating a billion tons of carbon from its supply chain (the annual emissions of Germany), in large part by working with its suppliers like Campbell and General Mills to source grain from farmers like Justin who have reduced their carbon footprint. Wal-Mart is also a leader in chemical safety: working to both reduce chemicals of concern in the products they sell and to provide greater transparency to consumers. I won’t wade further here into chemicals, except to say that the arguments over Round-Up and GMOS are rife with misinformation (which I try to clear up in my book). And that it’s vital for consumers to understand that there is no perfect farm. Every farmer navigates trade-offs. An organic farmer who plows to avoid using chemical weed-killers has to weigh the damage done to soil life by that plowing, just as Justin sometimes has to weigh the use of an insecticide against losing an entire crop to a pest and thus wasting all the land and water and tractor fuel that went into its production. The best farmers take the broadest view and seek the least harmful path at every turn.