Plant Chat: Edible Schoolyard New Orleans

Welcome to my Plant Chat Alisha Johnson Perry and Kerrie Partridge of the Edible Schoolyard in New Orleans (ESYNOLA). Alisha is the director of development for FirstLine Schools, where this wonderful gardening and culinary education program is offered to 2,800 students across four pre-K-8 schools in New Orleans. Alisha works closely with Kerrie Partridge, ESYNOLA’s program director, who is also joining us today on my Plant Chat. ESYNOLA brings the powerful tool of gardening to young children throughout New Orleans from grade pre-K-8, teaching hands-on gardening and kitchen skills in order to improve the long-term wellness of the students, staff, families and school communities involved. ESYNOLA provides garden and culinary education as well as special events open to the neighborhood to spread the love for gardening and empowering students and adults to grow and harvest their own food and to live a healthy lifestyle. I had the wonderful opportunity to meet Alisha and tour ESYNOLA last May. Read on to learn more about this special program!

What was the inspiration to begin this program in the FirstLine Schools?

Alisha: Prior to Katrina, FirstLine Schools, was operating under its original name, Middle School Advocates, and they created the first charter school in New Orleans, James Lewis Extension (later renamed New Orleans Charter Middle). Basically, Middle School Advocates started from the need of parents for their children to have access to a quality education. These parents collaborated with Jay Altman and local psychologist Tony Recasner to create an excellent school for children of diverse academic performance and educational backgrounds. The state granted that group of concerned citizens and parents the first charter in 1998. At that time, there were only a handful of public schools in New Orleans providing a solid, consistent and engaging education, and most of those schools only served students who tested well enough to get in, even factoring in some measurement of student I.Q. Meanwhile, the public schools for all of the other students not admitted in those top-performing schools had been disinvested in for many decades. At New Orleans Charter Middle, students participated in enrichment programs that allowed them to connect what they were learning in the classroom to real life experiences.

A gardening class offered by New Orleans Town Gardeners provided fertile ground for joyful, hands-on gardening experiences that taught students respect for living things and how to build and maintain a beautiful garden. The state recognized the success of NOCMS and offered Middle School Advocates a charter to turnaround Samuel J. Green, a failing junior high school. Then Hurricane Katrina hit, and the resulting federal flood destroyed 80% of our city, including the NOCMS school campus. Though Charter Middle couldn’t reopen, Green was able to reopen in January 2006, about four months after the storm. Alice Waters was one of many philanthropists visiting the city at the time, and Ruth U. Fertel Foundation’s Randy Fertel connected her with Tony Recasner, who was running Green. She offered that Green be the first site to replicate her Edible Schoolyard project model, which she had developed a decade before in Berkeley, CA. We built the garden, with help from New Orleans Town Gardeners, and the donors started coming. We now have gardens at the four K-8 schools FirstLine runs.

What was the initial response you received from students and faculty about the Edible Schoolyard? What is their response today?

Alisha: The program is so much different from when it started years ago. In 2006 we had one school with maybe 300 students, once families started returning to the city. The beautiful garden that was built was originally a teaching garden. We were just creating space for students and families to heal after enduring such widespread trauma from the storm. It was important for children to be connected to the soil, the environment and nature, and focus on the beauty of nature through butterfly gardens and flowering edible plants. In the early days, local farmers would come to the school, and celebrate seasonal harvests. The program has grown so much since then.

We now have four schoolyard gardens with outdoor classrooms that serve 2,800 students and two teaching kitchens.

We hope that students with exposure to our program continue to develop healthy relationships with food, nature, themselves and their community, because of the joyful and memorable classes and experiences they have had with us.

Every day students are expressing that garden and kitchen classes are why they like to come to school.

Children say that they feel more peaceful in the garden. We even now have a couple of students who have come up through the program who are pursuing culinary arts in high school and looking into majoring in agriculture and education in college, with some credit to their experience with Edible Schoolyard New Orleans.

What kind of power does this program have in students’ lives?

Kerrie: We start with students in kindergarten, through our Food ABC’s curriculum. We teach them to eat their way through the alphabet, using their five senses and reinforcing literacy skills. They get comfortable with new and unfamiliar foods and they try lots of new things. In our garden classes, we begin by getting them comfortable and excited to be in the space. We then begin to support them taking small risks — like being willing to walk past a bee, willingness to touch the soil and to hold a worm in their hand. They learn what it means to be a part of a garden community and how garden spaces can nourish and support. They are learning how to connect to themselves and the world around them through food and nature. They also expand areas such as leadership and critical-thinking skills, while also learning about the tools and the steps required to grow and prepare food. It’s a pretty powerful thing that at seven years old someone can hand them some tools and they can pick the food they grew with their garden teachers and friends, and then prepare a whole meal that they really like.

Alisha: This reminds me that children are learning to connect their gardening and cooking skills to a larger picture of their role in the greater food community. It is amazing to see the appreciation that they have for the chefs and farmers that come to their schools. Our Iron Chef Competitions, for example, give children opportunities to work alongside professional chefs to prepare a meal and compete against other teams of students in their class, all trying to create the most beautiful, tasty, and locally-sourced dishes. At the end, they get to shout-out their teammates for cooperation and focus, and thank the chefs for having patience and teaching them new concepts and creating new meals together.

Kerrie: Yes. This is the kind of experience that is threaded throughout our work with students. We teach the importance of social relationships as well as gratitude. We have really incredible chefs and farmers from around the city that volunteer their time and food, and the kids understand the importance of letting the chefs know how grateful they are that these chefs take the time away from their own restaurants to come and teach them.

Alisha: Ultimately, we hope that children with exposure to our program will make healthy lifestyle choices for their families when they become adults. Whether growing their own food, or buying and cooking fresh foods, we know that children are learning that they are in charge of what they eat, and that’s powerful.

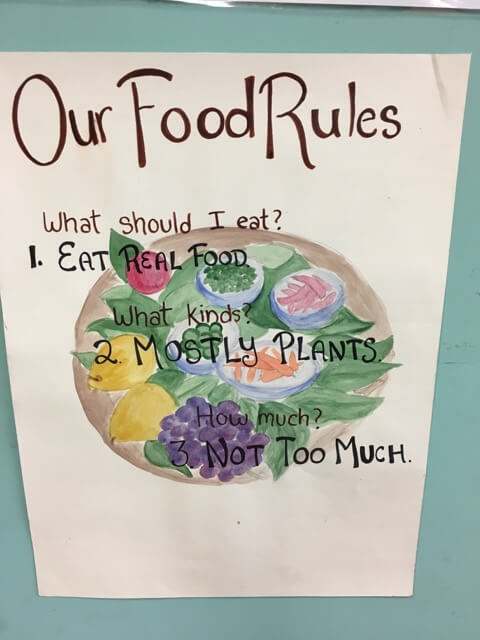

Kerrie: We teach the students the three simple rules for eating: Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.

Was there an improvement in student academic performance among the students after implementing this program?

Kerrie: We have a few different ways to answer that question, as we are still working on developing our evaluation strategy to capture the information we know is true. We have administered pre- and post-tests with student groups who had the opportunity to participate in our gardening and culinary classes. The data is pretty clear that when students have the opportunity to learn concepts in science class that are reinforced in the garden, their learning outcomes are much higher. That said, it is difficult to tease out the state and federal academic outcomes targeted, between what information they retained because of the garden versus what they learned in their traditional classes. What we know is that kids get really excited about science and environmental concepts, when offered hands-on learning opportunities and the space to contemplate and ask questions. I consistently hear classroom teachers say that students are bouncing ideas back and forth between what is happening in the gardens and kitchens and what they are learning in regular classes, so we know they are making those connections. We can’t wait to create and formalize the tools that better show the way children are living and learning in the gardens at FirstLine Schools.

Alisha: Also, we do have a quote from a student who suggested they would go on strike if garden class was no longer offered. Parents and teachers celebrate the impact the program is having on students, deepening their relationships with their peers, and even finding that those students who are often challenged in the traditional classroom setting are “stars” in the garden and kitchen.

Do the students create their own gardens at home based on the skills they have learned in school?

Kerrie: We have a good group of parents at each of our sites who are already motivated to garden. We are a city of gardeners for many generations, and though it fell off for a little while, many folks are really excited to reinvest in local growing. Parents will come to us and share that they are proud that they are already doing some of this at home, or have been inspired to do it because of what their kids are doing. There are definitely kids who get really fired up about bringing it home.

We have one gardening teacher that finds a lot of joy leaving seeds in the pockets of kids who talked about wanting to have gardens in their backyards.

What are some of the popular plants that are grown?

Kerrie: The one that comes to mind that I think is the most unusual is Thai hibiscus, or roselle. Our students are really into Thai hibiscus. It grows really well here, beginning at the end of the school year. They come back from summer break in August, and the plants are huge! I think this year we’ve tripled the amount of Thai hibiscus because there is never enough. You can eat the leaves and the flower pods and they’re very sour like super sour candy. The leaves are the same way. We have kids ask to take some home with them. They like most things we grow, like collard greens. They love them raw in salads, or to make wraps with them as the outside leaves.

Most of them are pretty open and happy to eat anything they saw growing and that they had their hands in.

Do you have any tips to help families start their own gardens at home and cook more with their families?

Kerrie: The first thing that comes to mind with that question is to start where you are. Start with something really simple and if you have gardening knowledge, go with that. Whether you start with one single pot, really relish in watching your plant grow and all the phases of it. I think it’s about being real with what you know and the space that you have, letting that be enough and letting that be the place where you start and get excited about it. Plenty of us who live in the city grow out of pots because many of us in New Orleans have courtyards, which are mainly patios. See what happens with containers and go from there; and, make friends with your local farmers! At least most towns have one small farmers market and they’re usually really happy to share their own knowledge.